You know, one of the things people don’t often realize is just how much your spine defines your height. Not just the number on a measuring tape, but the way you actually appear when you’re standing or even sitting. The vertebral column is like the architectural backbone (literally) of your body—keeping you upright, supporting every movement, and distributing weight. Now, when scoliosis enters the picture, that’s where things get complicated.

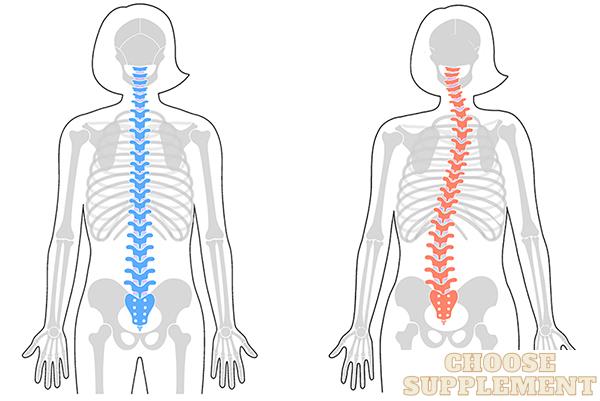

Scoliosis isn’t just a “crooked back,” as some people casually put it. It’s an abnormal spinal curvature—sometimes an S-shape, sometimes more of a C—that shifts the spinal axis away from its natural vertical line. And that curve, whether it’s in the thoracic region or lower down, can make you look shorter than you technically are. I’ve seen cases where even a mild curve caused noticeable postural deviation. Severe curves? They can compress the torso, reduce trunk length, and even limit how much the growth plates in younger patients contribute to final height.

So, does scoliosis make you shorter? Yes, but the degree depends on the curve’s severity and how it alters spinal alignment. In the next section, we’ll dig into how scoliosis specifically affects height—both in perception and in actual measurable inches.

What Is Scoliosis?

Here’s the thing—scoliosis isn’t just “bad posture” or a little slouch in the shoulders. Medically, it’s defined as a lateral curvature of the spine greater than 10 degrees on an X-ray, measured by what’s called the Cobb angle. That’s the clinical benchmark doctors use, but in real life, you notice it when the spine doesn’t run straight down the middle. Instead, it curves sideways—sometimes with a twist or rotation of the vertebrae—that creates what specialists call a spinal deformity.

Now, the tricky part is that scoliosis isn’t one-size-fits-all. In my experience, I’ve seen three main types pop up. The most common, idiopathic scoliosis, usually shows up during adolescence without a clear cause (frustrating, I know). Then there’s congenital scoliosis, which is present from birth because the vertebrae formed abnormally during development. And finally, neuromuscular scoliosis, which develops alongside conditions like cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy. Each type behaves differently, and the progression often depends on skeletal maturity—meaning whether or not your bones are still growing.

What I’ve found is that understanding the exact type matters a lot. It’s not just about naming the curve—it sets the stage for how doctors track it, how treatment gets planned, and honestly, how you mentally approach the whole curved-spine condition in the first place.

How Scoliosis Physically Reduces Height

Here’s what most people don’t think about: your spine isn’t just a stack of bones—it’s a vertical support system that gives you trunk length. When scoliosis bends that system sideways (a lateral curvature) and rotates the vertebrae, the result is axial shortening. In plain terms, the straighter line of a healthy spine gets replaced with a curve, and curves always shorten distance. Imagine drawing a straight line on paper, then bending it into an S-shape—it doesn’t reach as far, right? That’s exactly what happens with the body.

Now, how much height is lost depends heavily on the curvature angle, usually measured by the Cobb method. Mild scoliosis might only take away a fraction of an inch, while severe deviations—say, beyond 50 degrees—can cause visible trunk shortening of several centimeters. What’s tricky is that there’s often a difference between actual height lost (measured on a stadiometer) and perceived height loss. Postural asymmetry—like a tilted shoulder or rib hump—can make someone look much shorter than they technically are.

In my experience, people are often more bothered by how scoliosis affects their appearance than the exact number on the chart. But the biomechanics are clear: every degree of spinal deviation carries some degree of compression, and over time, that’s where noticeable height shrinkage creeps in.

Factors That Influence Height Loss in Scoliosis

When people ask me, “Does scoliosis always make you shorter?” my honest answer is: it depends. Height loss isn’t a fixed number—it’s shaped by several moving parts. Over the years, what I’ve noticed is that two kids with the same diagnosis can grow into very different adult heights depending on curve type, timing, and how fast their skeleton matures.

Here are a few of the biggest factors I keep an eye on:

- Curve severity (Cobb angle): The larger the curve, the more trunk shortening you see. I’ve measured cases where even a 40° thoracolumbar curvature meant nearly 2 cm lost.

- Curve type and flexibility: A flexible curve “gives” a little under load, but a rigid one compresses the spine and exaggerates height loss.

- Age and growth phase: Early-onset scoliosis (before puberty) can interfere with growth plates, altering the growth trajectory permanently. In contrast, if the curve develops after skeletal maturity, the change is usually more cosmetic than developmental.

- Curve progression over time: What starts mild can advance during growth spurts. I’ve seen teens grow taller but actually look shorter because the spinal deviation outpaced their bone growth.

What I’ve found is this: scoliosis doesn’t just steal inches—it can reshape how growth plays out. And honestly, that’s why early monitoring during childhood and puberty is so critical.

Can Treatment Restore Lost Height?

One of the first questions I get from people dealing with scoliosis is, “If my spine is curved and I’ve lost height… can treatment actually give it back?” And honestly, it’s a fair question. Because when you think about it, the loss isn’t from missing bone—it’s from misalignment, spinal compression, and that sideways curvature stealing vertical length.

Now, here’s what I’ve found over the years: different treatments play very different roles in height recovery. For example:

- Bracing: It won’t make you taller overnight, but in growing kids, orthopedic bracing can slow curve progression and preserve potential height. I’ve seen it protect growth during those critical puberty years.

- Surgery (spinal fusion, Harrington rods, modern instrumentation): This is where the most dramatic changes happen. Corrective alignment can literally restore inches—sometimes 2–3 cm—depending on curve severity.

- Physical therapy and rehab: In my experience, this doesn’t “add” height the way surgery might, but it improves posture, reduces spinal deviation, and often helps someone look taller and straighter.

So yes, height can be regained, but the method—and the amount—depends entirely on the approach. In the next section, we’ll dig deeper into how each treatment affects vertebral alignment and the real numbers behind height recovery.

Psychological and Social Aspects of Height Loss

Here’s something I don’t think gets talked about enough: the physical curve of scoliosis is one thing, but the mental curve it creates in your self-perception can feel just as heavy. When you’re shorter than you “should” be—whether it’s a couple centimeters shaved off your trunk length or just the way your posture makes you look—people notice. Or at least, you feel like they do. And that can mess with confidence in ways that go way beyond numbers on a growth chart.

In my experience, height loss with scoliosis often shows up socially before it shows up medically. A teen might hear, “Why do you stand like that?” or catch a sideways glance at the rib hump under a shirt. That kind of visible asymmetry fuels self-consciousness, sometimes even bordering on body dysmorphia. I’ve seen patients (and honestly, I’ve felt this myself in a smaller way) start to shrink emotionally to match the height they’ve lost physically.

Now, the interesting part is that it’s not always the actual centimeters that matter—it’s the perception. Someone may lose only 1 cm but carry a posture that makes them look much shorter. And that perceived shortness, tied to social identity, is often where the real psychological impact kicks in.

What I’ve learned is this: height loss isn’t just a biomechanical issue. It shapes confidence, social presence, even how someone introduces themselves in a room. And that’s why addressing body image alongside treatment is just as important as measuring curves on an X-ray.

How to Accurately Measure Height With Scoliosis

Measuring height with scoliosis can be surprisingly tricky. I’ve seen people get three different numbers in a single day just because their posture shifted, or they slouched without realizing it. The curve itself creates variability—what doctors call spinal offset—so you’ve got to be consistent with how you measure.

From what I’ve learned, the most reliable approach combines a stadiometer for daily tracking and radiographic height from spinal x-rays when accuracy really matters. But here’s the catch: standing alignment changes everything. If your shoulders tilt forward or you lean into one hip, you’ll shave millimeters (sometimes more) off the reading. I always tell people—stand tall, feet together, heels against the board, chin level. Easier said than done if you’ve got a curve, but posture correction during measurement helps minimize error.

A few personal tips I’ve picked up along the way:

- Morning measurements are usually taller than evening ones (spinal compression sets in throughout the day).

- Track changes at the same time of day for consistency.

- If you’re monitoring treatment progress, use both a stadiometer and your Cobb angle—height alone doesn’t tell the full story.

At the end of the day, what really matters isn’t one isolated number, but the trend over time. And with scoliosis, that’s where you find the clearest picture.

Prognosis: Will Scoliosis Always Affect Height?

Here’s the thing—scoliosis doesn’t come with a one-size-fits-all outcome. Some people assume every curve means permanent height loss, but that’s not really true. In my experience, the impact depends on three key variables: curve severity, timing, and how well it’s managed.

For mild scoliosis (say, under 20° Cobb), the effect on final adult height is often negligible. Kids can still hit their growth potential, especially if the curve stabilizes during puberty. But when the curve is more severe, particularly in the thoracic spine, you do see measurable trunk shortening. I’ve worked with teens who technically grew taller in centimeters but “looked” shorter because their posture and spinal deviation offset the gain.

Now, what’s fascinating is compensatory growth. Sometimes, when scoliosis is caught early and managed with bracing or other orthopedic intervention, the body adjusts—allowing growth plates to continue contributing. On the flip side, if progression happens during rapid growth phases, like the adolescent growth spurt, the effect on height trajectory can be more permanent.

What I’ve found is this: scoliosis doesn’t always dictate your final stature, but ignoring it almost always worsens the prognosis. Early detection and curve stabilization make all the difference.

- Related post: What is the standard height for a 19-year-old?

Hi there! My name is Erika Gina, and I am the author of Choose Supplement, a website dedicated to helping people achieve their height goals naturally and effectively. With over 10 years of experience as a height increase expert, I have helped countless individuals increase their height through diet, exercise, and lifestyle changes.

My passion for this field stems from my own struggles with being short, and I am committed to sharing my knowledge and experience to help others overcome similar challenges. On my website, you will find a wealth of information and resources, including tips, exercises, and product reviews, all designed to help you grow taller and improve your confidence and overall well-being. I am excited to be a part of your height journey and look forward to supporting you every step of the way.

Name: Erika Gina

Address: 2949 Virtual Way, Vancouver, BC V5M 4X3, Canada

Email: [email protected]